I Did Invent It (1914)

The bra, once kept tightly under wraps-both literally and figuratively-came out of the closet in the 20th century. In The Graduate, cougar Mrs. Robinson’s black, lace creation seduced the young Benjamin Braddock. Coo-coo-cachoo indeed. In Star Wars Princess Leia’s gold metal garment steamed up the cave of Jabba the Hut. Victoria Secret’s $10 million jewel encrusted treasure would make for a sweet ransom. These items of lingerie have become iconic, but the woman who launched the modern bra is shrouded in shadow.

Dorothy Parker quipped, “Brevity is the soul of lingerie,” and when a socialite put this statement into practice, the underwear industry was never the same. Its designer, Mary Phelps Jacob, nicknamed Polly, later known as Caresse Crosby, was born in 1891 in New York City into a world of power and privilege. She was a descendant of William Bradford, the first governor of the Plymouth Colony. Another illustrious ancestor was General Walter Phelps, who commanded troops in the Civil War at the battle of Antietam. Her great-great-great-great grandfather invented the steam train. The family divided their time between estates in Manhattan, Connecticut, and New Rochelle. She attended posh schools, and in 1915 was introduced to King George V at a London gardenLondon Garden party.

She married fellow blueblood, Richard Peabody, whose family had settled in New Hampshire in 1635, with whom she had two children. Dick returned from World War I a hero but shattered alcoholic. Mary had to not only endure living with her in-laws, but also with a husband whose nocturnal passion concerned an alarm bell above their bed. The shrill ring sounded whenever the emergency bell rang in the station, so Peabody could wake, dress in a firefighter’s uniform, and wear it while he watched the real firemen fight the flames.

As proof one should never underestimate a debutante with a fashion crisis, 21-year-old Mary was prepping for a society ball when the allure of her couture dress was compromised by the stiff corset peeking from under her gown. What’s a girl to do? Inspired, she told her French maid to bring her two handkerchiefs and pink ribbon that she sewed into a makeshift brassiere. Her creation was soft and light and conformed to her body better than the whalebone corset that made a woman look as if she had a uni-boob. Mary’s invention complimented the style of the time and was less restrictive than the previous Victorian fashions. She described her invention as “delicious” and wrote while still pressing “down one’s chest…so the truth that virgins had breasts should not be suspected.” Never one to shun adulation, Mary was mobbed after the dance by friends who wanted to know how she had moved so freely. She obliged their requests to make them their own undergarment. When a stranger offered to purchase one for a $1.00, she started a business selling brassieres-a name derived from the old French word for ‘upper arm.’ In her application for a patent, she wrote her product was “well adapted to women of different sizes and “so efficient that it may be worn by persons engaged in violent exercise like tennis.”

It was an invention whose time had come. Because of the War, the United States government requested women to stop buying corsets to conserve metal. Mary christened her new enterprise the Fashion Form Brassiere Company, located on Washington Street in Boston. With a staff of two, Mrs. Peabody began manufacturing her wireless wonder. However, while she managed to snag a few orders from department stores, her business never took off. The failure was because Mary had fallen hard for a man other than her husband, and soon nothing other than him held any appeal. Her office space provided cover for their trysts. She sold what she referred to as her sweatshop and her design for $1,500 ($20,000 in contemporary currency,) to the Warner Brothers Corset Company of Connecticut; it generated $15 million over the next three decades.

Harry Cosby, like Richard Peabody, was a war veteran and a heavy drinker. However, the difference was while Richard’s nocturnal habit was watching fires, Harry’s was causing friction between the sheets. His eccentric nature found a kindred spirit in Mary. He wore black suits, accessorized with black painted fingernails, and a black gardenia in his lapel. The bottoms of his feet were tattooed. He also had a habit of asking his lovers to commit suicide with him. His different drummer personality was not inherited-though his fortune was. His pious mother, Henrietta, founded the Garden Club of America, and his banker father, Stephen, was a former college football star who lived for his Ivy League and Boston society connections. His great Uncle Jack-AKA J. P. Morgan, had the distinction of being the celebrated banker.

The couple met in 1920 when Henrietta invited Mary to an Independence Day beach party. A few hours later, in a Tunnel of Love ride, Harry told Mary he loved her. Soon they were inseparable, oblivious to the blue-blood Boston scandal. In 1922 Mary divorced Peabody and married Harry. Not a fan of the name Mary, he suggested she change it to Caresse. In one of her sonnets, she ended with the words, “Forever to be Harry and Caresse.”

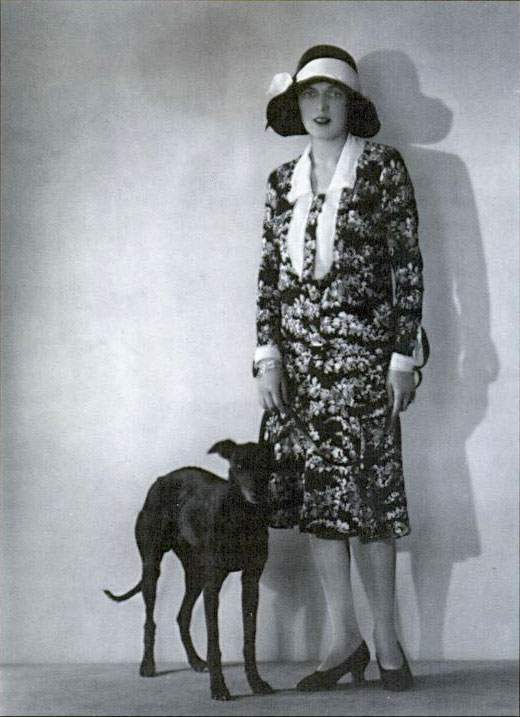

Two years later, to distance themselves from their wayward son, Harry’s parents arranged a bank position for him in Paris. In Europe the couple helped put the roar in the Roaring 20s and in terms of hedonism Harry and Caresse gave Scott and Zelda serious competition. They held Gatsby-like bacchanals that entailed seven in their gigantic bed; at another soiree Caresse appeared bare-breasted while Harry wore a necklace of dead pigeons. They dabbled in various eastern faiths, and were equal opportunity users of opiates, with a preference for opium. At other times the Crosbys drove around France in a green limousine where they, along with their dogs, (one of the whippets bore the name Clytoris) wore goggles. However, there was a cruel underbelly in their pursuit of pleasure. On holiday in Morocco, they took a 13-year-old dancer, Zora, to share their bed. Harry’s only known homosexual experience was with an under-aged boy. Other than this, Harry did not much care for children, which is why Caresse’s son and daughter lived at a boarding school.

Though their true vacation was endlessly reinventing their lives, they also had serious pursuits. They operated The Back Sun Press, a small publishing house that printed exquisite editions of early extracts from the most anticipated novels such as Finnegan’s Wake and works by D. H. Lawrence and Ezra Pound. Max Ernst, the surrealist painter and a close friend of Caresse, provided haunting images. The antiquarian book expert Neil Pearson stated, “A Black Sun edition is the literary equivalent of a Braque or a Picasso painting.”

After the Occupation, German troops commandeered the Crosbys’ French mill holiday home. To further the indignity, the Nazis painted over a unique curved white wall. Visitors used watercolors to leave their signatures or symbols: D. H. Lawrence drew a phoenix and Salvador Dali intertwined his name with that of a Pulitzer Prize winning American author. The surrealist used Caresse as a muse, and it is widely accepted she is the subject of his 1934 portrait. Another obliterated name was that of Eva Braun, who left hers alongside that of the Austrian big-game hunter who she had been seeing before she had fallen for the Fuhrer. Caresse lamented had she known the indignity that would have befallen her ‘guest-book’ she would have taken it with her. The comment was not facetious; taking a wall across a country or continent was the kind of over-the-top gesture for which the couple was known.

The Crosbys’ mad, bad Bohemian lifestyle, peppered with a rolodex of the cultural elite of the era, ended after the stock market crash. Unwilling to live a life devoid of conspicuous consumption- after Caresse declined to die with him- Harry shot himself and one of his mistresses in an apartment overlooking Central Park. His fellow suicide victim was Josephine Bigelow-Rotch, a young, recently married New Yorker. They had smoked opium and drunk a bottle of whiskey prior to ending their lives.

Harry’s death devastated Caresse, but it also served to liberate her from her libertine ways. She started pro-peace movements and campaigned for prisoners of war. However, she continued with her old habit of travelling the world and courting the famous such as T. E. Lawrence, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Allen Ginsberg. In Paris she fell in with Henry Miller and Anais Nin and helped them with their writing of erotica. She eventually returned to the United States, and in 1937 married third hubbie, Selbert Young, 18 years her junior, a former football player and movie star. They moved to Washington, D. C. where she opened an art gallery and started a magazine, Portfolio. After the failure of her third walk down the aisle, she spent her final years in Rome where she planned to launch an artist colony. She passed away in Italy in 1970 from heart disease.

Warner Brothers might have got the better end of the deal, but Caresse held on to her glory. Her proudest boast, “I can’t say the brassiere will ever take as great a place in history as the steamboat, but I did invent it.”