A Crazy Plaid (1876)

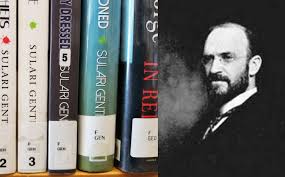

For Marilyn, diamonds were a girl’s best friend, but for librarians the Dewey Decimal Classification is their guru. Want a book on fairy tales? (398.2,) rock music? (781.66,) literature? (800.) But the founder of the system, Melvil Dewey, defied classification.

A most peculiar man was born Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey, in 1851, in Adams Center, New York. The area is known as the “Burned-Over District” due to the number of its reform movements: Mormonism, the Shakers, abolitionism. Joel and Eliza Dewey were shoemakers who struggled to support their five children. With Marie Kondo precision, Melvil, organized his mother’s pantry. Another passion was books, and he walked ten miles to the town of Waterton to purchase an unabridged Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language. The lure: it organized words into alphabetical lists. His obsession with the metric system, (he tried to make America convert to this system,) was his December 10th birthday.

As a teen, Melvil gave up his aspiration to become a minister in order to devote himself to public education. He enrolled in Amherst College where he obtained a position in its library that he viewed as a citadel of disorder. His aha! Moment occurred during a church sermon where he envisioned a system using letters and decimals-as per his mania for ten- for organization based on content. Approximately more than 200,000 libraries in 135 countries use his system. However, not all his ideas met with approval. A proponent of economy, he changed the spelling of his name from Melville to Melvil, Dewey to Dui. Before his departure, he wrote to the university, “Sum day, may it be my happy lot tu pruv how great iz the love I bear yu…”

In 1876, Melvil moved to Boston and married Annie Godfrey, with whom he had son, Godfrey. He organized a library convention at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia that led to the creation of the American Library Association; he also founded the American Library Journal and established free libraries for the blind and children.

While working at Columbia University, Melvil instituted a school to train librarians, one open to women. The reasons for this progressive move were the school could pay females lower wages, and Melvil could seduce his students. Applicants had to submit photographs so he could gauge their attractiveness. As he explained, “You cannot polish a pumpkin.” Dr. Dewey described his stenographer as a “dainty litl flapper.” Columbia decided to close the program, not over sexual harassment, but because they disapproved of admitting females.

The next venture was to open a health resort in Lake Placid, New York. He charged $10.00 for membership, and guests had to turn off the lights at 10 p.m. Another stipulation: no Jews or blacks. The racism was in keeping with the Dewey Decimal System that marginalized non-Christians and blacks. He categorized homosexuals under Abnormal Psychology, Perversion, and Derangement. The venture proved so profitable that it served as the site of the 1932 winter Olympics.

His private peccadilloes became public on a trip to Alaska sponsored by the American Library Association where he hit on four women that led to his resignation of the organization. (His daughter-in-law left his home because of unwelcome overtures.) At age seventy-eight, he had to pay his former secretary at the Lake Placid Club $2,147 for sexual harassment. Melville’s mea culpa: He was “morally ryt,” his detractors were merely “old maids.”

The founding father of libraries remains hard to categorize: he devoted his life to literacy and yet was a sexual predator and unabashed bigot. Dorothy Parker’s poem, (810) expressed the concept of moral ambiguity, “And good and bad/Are woven in a crazy plaid.”